Originaire de Vancouver, Paul Kirby arrive à Montréal en 1966 pour étudier à McGill. Il se lie rapidement avec un certain nombre d’activistes, notamment des « draft dodgers », et profite de la vague des journaux underground pour fonder Logos avec quelques personnes. Un de ceux-là est le Montréalais Robert Kelder, très versé dans le théâtre, particulièrement celui du Living Theatre. Sa sœur Adriana sera introduite dans le groupe, qui vit désormais en commune, au cours de l’année 1968. Étudiante à l’école des Beaux-Arts, elle se liera avec Paul Kirby.

L’histoire très mouvementée de Logos verra passer facilement une centaine de personnes, mais à la fin de 1968 et au début de 1969, le journal repose essentiellement sur le couple Kirby-Kelder. Ils le laisseront alors au soin d’une autre équipe pour fonder une troupe de théâtre itinérante, la Caravan Stage Company. Le film de Dorothy Todd Hénaut, Horse-Drawn Magic, disponible sur le site de l’ONF, capture l’ambiance de cette troupe déjantée, un peu circassienne, en tous points héritière de l’utopie esquissée dans les pages colorées de Logos.

C’est de son bateau amarré à Brooklyn que le couple nous a parlé en décembre 2014, retraçant son aventure montréalaise. Le récit est largement pris en charge par Paul Kirby, initiateur du projet, mais Adriana « Nans » Kelder a suivi tout du long, corrigeant à l’occasion les dates, les noms, les lieux qui se sont perdus dans la brume du temps. Quant à nos propres interventions, nous les avons gardées au minimum.

ACTE 1 : Les draft dodgers. Noam Chomsky.

Premier numéro, première saisie.

Paul : I came to Montreal around 1966, and I was doing graduate psychology studies at McGill. In the process, I got involved with a friend by the name of Chandra Prakash. He was a graduate student in English Literature. We were very much against the Vietnam war, involved with Palestinian rights and human rights activities in Montreal. We made some proposals to the liberal government, and we met a couple of ministers, regarding Canada’s position on Vietnam War. We discover that they were saying one thing in public, and then in private they were backing away from any kind of commitment they made. It was window dressing. What they were saying and what they were doing, it was complete reversal of positions. In the process, we connected with Laurier Lapierre, who was a journalist at the CBC, hosting a program that was called « This hour has seven days ». It was one of the best television news program, and was took off the air because it was considered too radical.

That evolved into making contact with Noam Chomsky. He came to McGill University and talked to the combine psychology and philosophy department. Another friend I had meet at McGill was the head of the philosophy department, who was again another radical in his own way. We had a number of meetings with Chomsky privately, and he suggested that we set up a hostel for draft dodgers and army deserters. Most of them went to Toronto, but some of them came to Montreal and they had no place to stay or any reception committee. So we set that out, in conjunction with a man by the name of Nardo Castillo. We worked with them and ran the place down on south of Atwater. It was called the Gandhi house and it ran for a number of months. In the process, we met different people and connected with artists from United States.

It was the beginning, at the times, of underground press. There was the Berkeley Barb, The Village Voice, The LA Free Press, and few others. We formed a committee of five people, among them Chandra Prakash, Adriana’s brother Robert, John Wagner and Alan Shapiro, and put out a first edition in the fall of 1967. John was our cover artist and made four or five covers through that early period ; he eventually went to Arizona to concentrate on his art. Chandra also got less involved, since he had his PhD going. In the while, I quit McGill, so the newspaper felt to Robert and myself.

It was our contention from the very beginning that we couldn’t get a license to sell a paper on the street because it was a restriction of freedom of the press. Therefore, we needed a complete freedom to sell and distribute anything we wanted as citizens on the street. To require a license was a vehicle for the authorities to restrict what could get on the street and ultimately it was a restriction of freedom of speech, which we, of course, were upholding by any way we could. Nevertheless, Chandra and I and a couple other people got picked up by the police, got grilled and asked about the paper.

1924 : That was for the first edition?

Paul : For the very first edition, in October 1967. The Montreal police were heavy-handed on the paper and the people selling the paper.

1924 : Did they looked like hippies or the matter was really selling the paper?

Paul: It wasn’t the people, cause there was a whole range of people selling it. At some point, even playwright David Fennario, mostly known for his later play Balconville, was dropping by to sell the paper.

Adriana : It was mostly young people, obviously. There was also a lot of draft dodgers in Montreal at the time and it was one way they could make some extra cash.

Paul : We didn’t really keep track of how much money was brought in as long as there was enough to print the next issue. Some people came back with the money, but other were able just to survive by selling Logos, and it was fine with us.

1924 : Where did you live?

Paul : At the time, we were still at the Gandhi house, on Saint-Antoine street, near Atwater. I lived there – Nans and I still hadn’t connected – and Chandra was in the McGill student ghetto. Rob lived in the same area.

Just after the first issue, we acquired a loft on 3666 Saint-Laurent, above a bakery. I think we put out three or four issues out of that loft, and then we rented a duplex on the corner of Coloniale and Prince Arthur, right beside a fish market. We had the office in the basement, and living quarters in the others floor. That was the first time we all moved together, so it became known as the Logos house.

ACTE 2. Politique & psychédélisme. Création du Voyage. La convention démocrate de Chicago en 1968. Ça se durcit.

1924 : From the very beginning, Logos took a strong stance in favor of Québec Independence. It must have shocked?

Paul : Perhaps, yeah. It became apparent to us, with the Quebecois Liberals who had gone to Ottawa under Trudeau, that any kind of aspirations that the Québécois had for some kind of independence, was it full throttle independence or some sort of special consideration under the Canadian constitution – anyway, Canada was still a dominion at the time – was doomed to fail. It became clear to us that these guys were just there to grab power.

At the same time, we became friends – myself in particular – with Jacques Larue-Langlois, who was a professor at the Université de Montréal. We had a number of discussions about Québec, the liberation movement, the FLQ, and he wrote a few articles for Logos. In January 1968, there was this cultural congress in Havana. He went there, covered the whole thing that was featured in the fifth issue.

Subsequent to that, we decided that we would declare unequivocally and a hundred percent in favor of Quebec independence as a newspaper. We issue a declaration of separation and Le Voyage was created out of the split. We trumpeted the fact that we did it as a wish fulfillment from both sides and that there was no acrimony at all ; in fact, we were supporting each other, although Le voyage didn’t last very long. From that point, we always championed Quebec liberation and Quebecois liberation movement. And I still do!

1924 : Highly political in the first issues, Logos evolves in a psychedelic manner with a stunning graphical prowess. What cause the transition?

Paul : In 67-68, there was sort of a huge coming out of what was dubbed by the mainstream media as the hippie movement, but it really grew out of the street. Its genesis was in the student uprising in Berkeley, and the spreading of the Student for a Democratic Society (SDS). It took a more colorful turn with the so-called hippy movement. The identification with the drugs and the music was part of the whole culture, but as far as we were concerned, it was a vehicle for us to reach out to more people, to garner support and rally the troops. We were able to use the psychedelia to bolster the readership and circulation of the paper. So it wasn’t like we completely identified and ship our political base ; but we opened our political base to encompass the more flamboyant psychedelic movement that was reaching its pinnacle.

1924 : From what we get, it was selling well.

Paul : It was mostly sold on the street. We also had a few bookstore, record store, coffee shops and other outlets where it was sold. It achieved some sort of notoriety, and the mainstream media were attracted to it. At that time of Logos history, I started doing a lot of interviews ; we went two or three times on the CBC with Jacques Larue-Langlois.

1924 : You were also the inspiration for a film made by Robin Spry?

Paul : Yeah. He had made a film for the NFB about the Toronto scene called Yorkville and he came up with his idea. A guy we knew who was a playwright wrote a film script based on my position, more than my character, and the fact that I was the editor and publisher of Logos. Robin asked me what direction we should take and I said that what he needed, in order to make this film work, was to go to Chicago, to the Democratic Convention in the summer of 1968. And so they did. They took the whole crew and the actors, and filmed them among the demonstrations and the police violence.

It became a very critical point in the American politics ; and it led to the eventual police crackdown on any liberation or cultural movement at a time where the Black Panthers were uprising. It became way more aggressive and violent, and the FBI got completely paranoid. On our side of the border, I think the Montreal police realize more deeply what we were doing and began to harass us and tried everything they could to close it down.

The whole epoch of the sixties led to that crescendo in Chicago and at that point it really became an intense struggle with the police – which was a sort of tragedy in itself, because we were completely overtaken by fighting legal battles instead of being able to create interesting artistic elements in the paper. We continued to do so, but I think a lot of underground papers had to go a little bit more mainstream in order to survive and by doing so, they lost some of their political heft and consciousness, as it became apparent in The Georgia Straight (Vancouver) or The Village Voice (New York).

1924 : You took the other way, with a naked woman – Adriana – holding a miniature policeman in her hand on the front page of number 7, published in may 1968. That was a clear provocation that gave you some trouble.

Paul : We had troubles with every issue from then on. As I said, it was the real beginning of the crackdown. We were charged with publishing obscene material with that one, and then the next one we were charged for the same thing again, and all this time, anybody who sold it on the street was being arrested right away.

That was when the editor and publisher of the Montreal Star, Frank Walker, became to realize that this was a travesty of the freedom of the press and, as an old lefty from the thirties, he became sort of our legal benefactor. He, the paper and their lawyers supported our legal fights monetarily and editorially.

Walker approached us in the summer of 68. He heard that we were on our way to the first ever Toronto rock festival and he asked us to publish an eight pages supplement in The Montreal Star. He gave us press passes and eight or nine of us went to Toronto, where we stayed at Rochdale, an apartment building which was the epicenter of anything interesting in Toronto, from artistic to political proposals.

ACTE III : Extra! Extra! Mayor shot by dope-crazed hippie!

1924 : And then came, in November 68, the infamous fake Gazette issue.

Paul : By that time, we were getting quite frustrated by the illegality and the injustice the Montreal police were dumping on us. We always noted that the Montreal Gazette published an evening edition that came out around 9:30 every night, particularly on hockey nights. They were selling papers like mad. That was a huge income for them. They had these kiosks all over the place and also people selling in front of the Forum, or St-Catherine Street and downtown. And we knew they didn’t had a license to sell the paper on the street cause even if you wanted one, you couldn’t get it. There was no such animal. It just didn’t exist. If you’d go to City Hall at the time to ask for a license to sell a paper on the street, they just would say, « Sorry, we don’t have one. There’s no such thing. »

So we became quite incensed, obviously, at the disparity of treatment. We were the Second Citizens. They were the First Citizens. The situation was getting pretty dire, because we had a lot of people in jail. We were spending inordinate amounts of time in the halls of justice, getting them bailed out of jail, and then doing the court cases. The interesting sideline of that whole thing is that I got to know the chief prosecutor quite well. At some point he said that when all this came to some kind of closure, he was going to have a picture of me on the wall as one of his more distinguished graduates. I never gave him that picture.

In the process, we – it was pretty well Adriana and myself – decided that we would fight back, with as much inflammatory venom that we could conjure up on the newspaper. We wanted ultimately this whole thing to go up to the top, and it went to Drapeau. We started thinking about publishing a mock issue of the Gazette, sort of in the lines of Orson Wells and the invasion of the Martians, using satire in an extreme way in order to make our point : that there were two levels of justice operating in Montreal, and somewhat in the rest of Canada. That’s where we came up with the idea of publishing the mock paper.

We also wanted to put out an inflammatory headline that was basically, completely satirical. We realized that the only time they ever put out « extras, » what they call an « extra edition, » was when somebody was assassinated. Looking at the archives of The Gazette, which we did quite extensively before we even started creating the issue, we noticed and copied some of the material that was on the front page and second page of both Kennedy’s assassinations and Martin Luther King’s. So then we proceeded to do it.

We put it all together. We designed it all, wrote it all, which we did with every paper, but we stayed pretty tight-lipped about this one, because we sort of anticipated there could be a pretty extreme reaction. And we had already been in jail so many times, and charged with so many so-called offenses, that we knew we were going to get pretty slammed by this one. We created a strategy to make as much noise as we could with this issue. We realized that the best way to do this was to bundle these papers and create really a piece of street theatre with them. So we bundled them all up and labeled them with metro newsstand labels.

We actually had maybe 50 papers in a bundle, and we would run into the Metro station, and yell at the top of our lungs, « Mayor shot! Mayor shot by dope-crazed hippie! » Then we would run and drop the bundle on the top shelf of these newsstands, and then run out still yelling, « Mayor shot! Read all about it! Extra! Extra! Extra! » Then we also had a crew of people whom we had picked as come of our more adventurous street-sellers. They took bundles of the paper, and we told them to keep going : « Don’t ever stop, just keep selling the paper and just keep moving. » So they fanned out all over the downtown area.

In the while, Nans and I were with a guy named Peter. He had a little Volkswagen, Karmann Ghia or something, and we piled all of it. We had two cars and two teams. Nans and I were on one team with him. The fun part of this whole thing is that he was not part of the sort of Logos inner core at the time, but he heard about it and he got so excited, he really wanted to be involved in this. So we solicited him as a driver.

The real kicker was that we did that to a couple of radio stations. Primarily we took it to the main CBC building on Sherbrooke, near Atwater. We rushed in and dumped some papers on the front desk, and we dropped some papers in the foyer as well, and then came out. One of our points, beyond the local Montreal issue of selling a paper without a license, was that newspapers are basically headline-driven. The content is held hostage to the headline, and it’s often false, or certainly exaggerated. That’s why we put out that explosive headline. What happened was that CBC, in its entirety, both radio and television, all over English Canada, completely closed down all their programming and started bringing in these experts, and commentators. It was live on television across the country about this horrible, horrible assassination, or shooting.

1924 : They took it for real?

Paul : Yeah! And of course, if you’ve got a copy of that, you’ll know that you just have to read, or open the first page, and you know that it’s a mock issue. It went live. This is what we discovered in the trial, but also friends at CBC told us this. It went live across the country. At the time, my parents were alive and they were in Vancouver. They told me this. I think they both were watching something on CBC and suddenly it cut to this incredible story of the mayor being shot by a drug-crazed hippie in Montreal.

In those days they didn’t have too many machine-gun-toting security people at the front door. They had these kind of quite retired, aged soldiers, who were called « commissionaires » and were doorman and quasi-receptionists at government buildings. So one of these guys was reading the paper, and laughing and having a great time reading the paper, the Logos paper, the inside of the paper. There was a television in the foyer, and at one point he just sort of looked it over, after pulling his head out of the paper, and he saw that they were on. The CBC national television was on air discussing these whole, horrible events. He laughed and he went running up to the front desk and he said, « Look what this is! This is Logos! This is a joke! This is satire and you guys have fallen for it! »

The same thing was happening in the radio stations, and unbeknownst to us, what also was happening was that the publishers of The Gazette were infuriated that this had happened. They had their editors call in everybody, like the entire staff of The Gazette paper, including the people that ran the presses down below, and people that drove the trucks, reporters, photographers, and they demanded that they all come down to The Gazette building, at that time of night. It was probably like 9:30, 10:00 o’clock. They all came down. The publisher got up in front of the whole crew, and they held up the Logos paper. They said, « All right. Who did this!?! Who did this!?! »

1924 : Did they think it was an inside job?

Paul : Yeah! They did, yeah! There was a reporter from the United States who was really a big fan of ours, Phil Winslow, and he was a Gazette reporter. There was quite a bit of laughter, because a lot of people had actually picked up copies somewhere on the street or something and they knew it was Logos. And they couldn’t believe that this publishing owner/editor hadn’t actually read past the headline! He stood up and he said, « I think if you open the first page, you’ll see who is responsible. » So they opened the front page, of course, and immediately saw that it was Logos. And then they just had to eat crow like crazy. They just actually totally believed that somebody, that one of their, or a group of their staff, reporters, and writers, had turned the table on them.

1924 : Well that was a frank success!

Paul : Yeah, totally. It was way beyond anything we could have imagined, in terms of success. Of course, then what happened was during all the distribution and aftermath of it all, they were so embarrassed. Their egos, the police, the mayor, they were all just completely discombobulated and completely distraught over the fact that we pulled this off. So they immediately issued a complete, what they call in English, an all-points bulletin, where they sent squad cars everywhere, all over the city, and police officers armed with guns to grab any Logos person at all and to raid the Logos House.

You know, you take this all out there and you just don’t know what kind of impact. In your dream state you think, « Oh, this is going to have a huge, significant impact. It’s going to change things ». But we didn’t anticipate, in our wildest imagination, that they would put out such a repressive reaction, and that they would really go across the country with all the crazy news. I got a phone call from the same reporter that I was telling you about at The Gazette, Phil Winslow. They had just broken up from that meeting that the publishers had called and he phoned us. He had gone by a desk and they had police scanners on their desk. He said, « Get out of there! They’re coming! They’re coming to the Logos House! » He said, « Get out of there! Get out of there! »

So we all packed some stuff and ran out. Nans and I went to a friend’s apartment about a block away and the rest of the people just disappeared into other people’s homes. Then the police arrived, and according to the neighbors, they came up in a lot of cars with all their lights blazing and guns drawn, and just started smashing doors down. There was a reporter from some radio station who had pulled up just before they had arrived and they almost shot him. It was that close. He had to duck down and scream that he was a journalist.

And it actually went on. Every hour, we were at the top of the news. Paul Kirby and his lover, Adriana Kelder, were in hiding and the police were looking for them all over the street. Actually for the first five or six hours, there were of course, rumors that we had crossed the border, and so on. A lot of this we didn’t find out about until the trial, which was a year later. We did find out how much of an uproar that we actually created, and it was quite satisfying. But we didn’t realize the extent of actually what we had created until the year later when we kept hearing stories. They brought all these people in to testify at the trial. It was quite illuminating to hear all these stories and realize how much we had pushed their buttons.

ACTE IV : Procès pour sédition. John Lennon, Buckminster Fuller & Alfred Pellan. Partys au punch électrique.

1924 : That’s quite an adventure. I’d like to know about consequences and how it has ended.

Adriana : Consequences? It got us kicked out of Montreal!

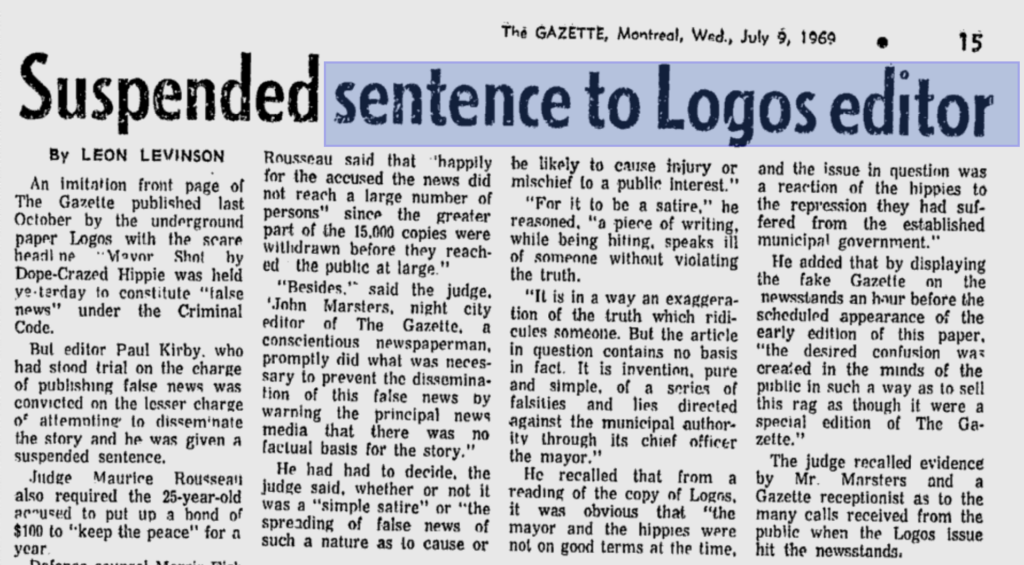

Paul : What happened was that the trial of the Gazette issue, eventually I was charged with sedition.

1924 : No less?

Paul : Yeah, and apparently there have only ever been two people charged with that crime in Canada. So I’m one of the two. Fortunately I had a really good lawyer by the name of Morris Fish who eventually became a Supreme Court judge in 2003. He basically told us that it was pretty well a lost cause at that stage, but he wanted to take it to the Superior Court and so he did. What happened was that I was eventually found guilty and I was given a 2-year probation sentence, or suspended sentence, and I had to put up a peace bond.

1924 : A peace bond. What is that?

Paul : Yeah, it was pretty crazy. I was given, I don’t know how many days, 10 days or something to put up a peace bond or else I would have to go to jail for the 2 years. And in doing so, I had to pay a heavy fine and to commit myself to keeping peace, not doing anything at all basically in the city of Montreal. We, at the time of the actual sentencing, as I said, had anticipated being found guilty and having to deal with it, so we had planned an escape to get out of Montreal. We basically left right after the sentencing, and in the process, that’s when we were planning on starting the caravan.

Actually we left very soon. Before we were sentenced, there was a number of other trials going on as I mentioned. We were already charged with two counts of publishing obscene material and about 35 counts of selling a newspaper without a license on the street. Even though the lawyers were doing everything pro bono, for free, we still had to raise money because there were court costs.

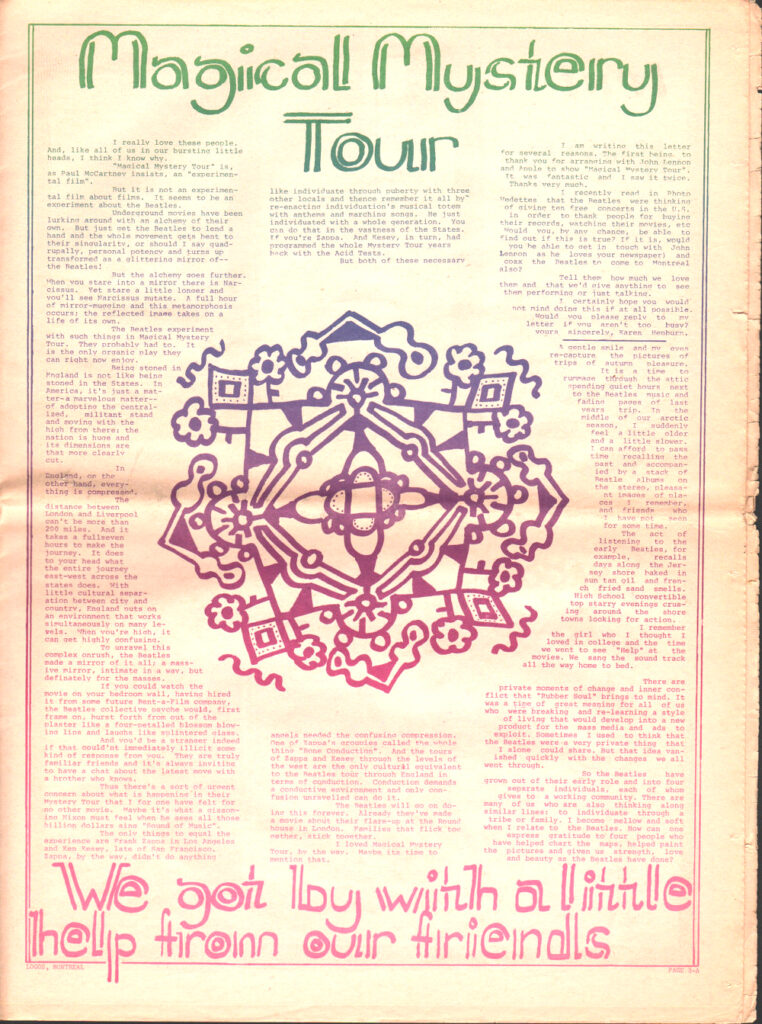

So one of our people was from England and his name was Julian Harding. He at one point informed us that he knew somebody who knew somebody who could get to John Lennon. They had just made the film Magical Mystery Tour and it had shown only on UK television. So together with Nans, and I, and three or four other people and him, we made a presentation to his friend to get to John and ask him for the Magical Mystery Tour film so we could show it in Montreal and use it as a benefit, as a fundraiser for all these trials. Lo and behold, one very cold winter morning, there was a knock on the door at Logos’ house. This guy hands us a big package, a film. So we took it inside and opened it up and there was a note inside saying, « Paul, and Nans, and Logos, good luck. Stay out of jail. Your friend, John. »

1924 : Fantastic!

Paul : Yeah. It was great, but you know in those days, there were so many people that we were connecting with. And the world hadn’t evolved into this disingenuous worship of celebrities. So we just took the note and said, « Oh, that’s really nice, » and then we threw it in the fire. And then we proceeded to make plans to show the film at Sir George William, McGill, and at University of Montreal. We felt that was the best avenue for us to reach people. It took us about two months to organize all the showings and we presented the film. I think we did about four or five nights at each university, and we made enough money to keep the lawyers happy and also to put out a last issue of Logos, as I said, because we knew we were on our way out.

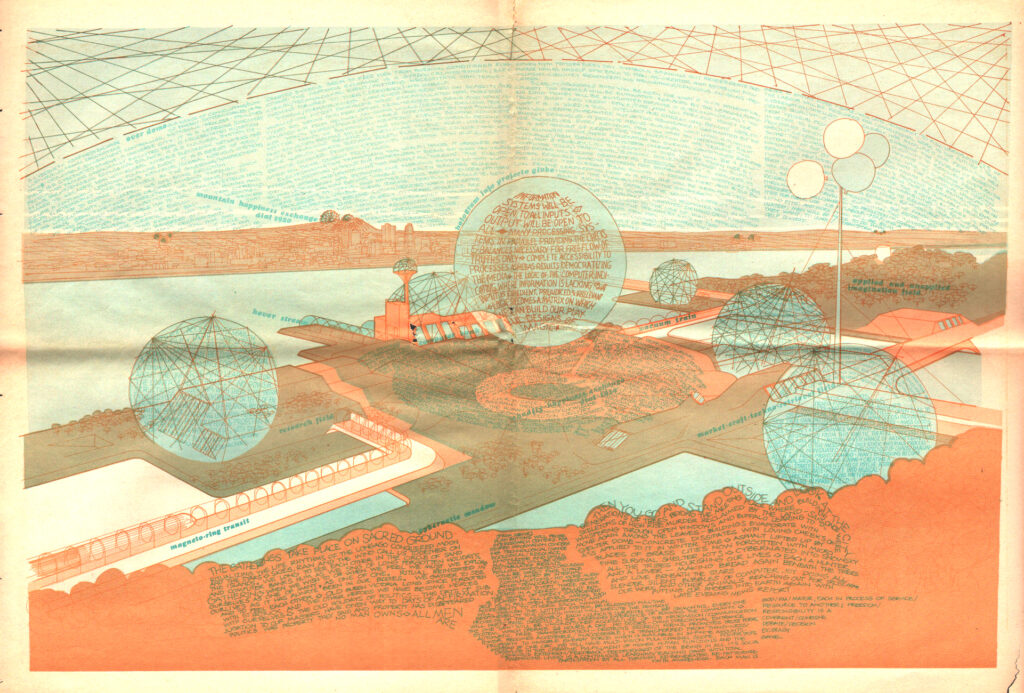

1924 : It was number 10, famous for its adventurous layout.

Paul : Yeah, we really poured a lot of energy into it and wrote a lot of really interesting articles. We conceived a thing called the Cybernated Happiness Exchange Center. We turned the Expo 67 site and we divided the whole country up into these little bio-regional governments. This is just when computers were really starting to surface. There was no such thing as a personal computer and only the rare company had a computer, but IBM was pushing it. They were the only ones with any kind of computers, and these were huge things, the size of a room. Anyways we recognized the beneficial potential of it.

So we created this thing called the Cybernated Happiness Exchange Center, which was, in effect, a government for that region of Montreal really, not for the city of Montreal, but we broke up Montreal into these bio-regions and then the rest of the country. It was inspired by US thinker and architect Buckminster Fuller. In the Expo 67, the US pavilion was a geodesic dome, and it was the talk of both Canada and the United States.

1924 : It’s still there!

Paul : I’m sure it is, yeah. Anyway that’s his design. He was a very, very forward-thinking guy and he was one of the earlier people capable of saying that the globe was warming. At that time, it was warming not very much, but he could see the dangers coming on. He put together ten volumes of his thoughts on everything from recycling to new energy sources and architecture, not really anything political but just a lot of design stuff. He invented a car called a Dymaxion car, which I don’t recall too much about it, but it was definitely an electric car.

Anyways somewhere along the line, I met this young architect. We were all in the same sort of milieu in Montreal, and he informed me that his architectural firm had these connections to Buckminster Fuller and his boss was one of Buckminster Fuller’s friends, and he had these ten volumes of Buckminster Fuller’s combined aggregate of thinking and designs and everything. So he brought these over and he and I, over a period of about a month, poured over these books. And in the end, we designed this Cybernated Happiness Exchange Center.

In the design, we had magneto trains and vacuum trains. So everything ran on the sort of sustainable energy principles. Then there were a bunch of other cultural things in the book as well, but that was kind of the thrust of that issue. Given that we were on our way out, we wanted to pour everything we could in terms of all our thinking, both politically and culturally and socially into that, and we did.

1924 : And it was time to leave Montreal for good.

Paul : At the time, we were in the process of creating our plans for our own little departure and also the work that we envisioned on continuing with the circus troupe theater troupe. So we organized this big event in Moose Hall on Park Avenue, in April 1969. It’s advertised on the back cover of number 10.

Somewhere along the line, we got approached by a guy in the United States who wanted 20,000 copies of Logos. Logos was starting to have quite a reputation in the United States and England. He wanted to be our main distributor in the United States. So we talked to him on the phone a couple times and we said, « Sure, that sounds great. » So he became our distributor, but actually he was an acid dealer. It was his main source of income, but politically he wanted to be a media distributor. So he did get 20,000 copies of one of our late issues. And then he decided that he wanted even more. So the first couple issues we packaged up and sent to him, and then he said, « I’m going to come up to Montreal and pick them up. »

Anyway we did this party and it was a great event. We had many bands, and we were doing light shows, and we had fortune tellers. We sort of encapsulated some of the stuff that we wanted to have in this planned circus. Lo and behold, a friend of ours, Dorothy Todd Hénaut, who made the National Film Board Film on the caravan called Horse Drawn Magic arrives with the director of the contemporary museum at the Expo site, and at the same time our distributor came. So we went off and we transacted the business deal, and he had about three vials of LSD with him. So he very quietly, with a nod from me, dumped it in the punch. From that moment on, that was one of the greatest parties in Montreal.

About two hours later, the museum director is at my side for quite a bit of time and is basically begging me to come and do this at his contemporary art museum. What was interesting was that he wanted us to do this for the opening of Québécois artist Alfred Pellan. It was a big deal. The minister of culture was coming and all these so-called dignitaries of the cultural world were going to be there, including a whole whack of people from the arts councils and the foundations and the high society of Montreal. He was really, really adamant, and I thought it was quite an interesting proposal so we took him up on it.

So we did and this was quite a bit more organized. We had a lot of bands, and dance pieces, and music and interesting little theatrical elements. There were two huge rooms in this gallery, museum, and we just took over all these rooms. We had about 50 people, I think, from our huge gang of artists and technicians and activists from the street in Montreal. It was probably the second wildest night in Montreal, and actually the Montreal Star wrote a big article about it claiming that Montreal had – what did they say – something like finally moved into the 20th century and had all this really interesting art, and these light shows, and this music, and dance, etc. Everybody had a great time. There was another punch. It wasn’t quite as freely distributed, but that also added to the boost.

ACTE V : La Caravan Stage Company.

1924 : And then you went your way with your newly created theatre company, The Caravan Stage.

Paul : Nans and I left Montreal after turning the paper over to Jean Nantel and some other people. We had a Volkswagen bus that we bought, and as I mentioned, there were plans for us to go out west and sort of establish a base, and then a bunch of other people were going to come out and join us. Brian Clark did and a couple other people, so three or four other people came out, and we were going out to start a kind of traveling troupe of circus and artists and political and activists. And we were going to travel around in buses and various other vehicles. In the process of going out to the West, this Volkswagen van that Nans and I were traveling in broke down three times and we had to rebuild the engine three times in various interesting circumstances, but the result of that was just a shared horror of having to deal with trucks and buses.

Nans actually suggested, « Maybe we should get horses and wagons and travel around that way. » We also liked the idea of the ecology of that and the energy of that. So when we got to B.C., we started to work on it. The whole idea was to build a bunch of wagons, and put together a troupe of people and spend two to three weeks in a community and develop a show particular to that community, and in the meantime also do a bunch of other workshops in various crafts and culture and politics and promote the whole idea of what we espoused in that last issue number 10 of Logos.

When we finally got to Vancouver, at that point we were pretty well set on creating a horse-drawn circus caravan. For some reason, we ended up in Victoria and we set up a base there. There was a guy that ran the Victoria Art Gallery. His name was Colin Graham. He basically, along with a lot of other art gallery directors had heard all about this evening in Montreal. So it was really quite funny. He was very Victorian in his manner and his speech.

I think he’s originally from England, but he was quite determined for us to do this in his gallery, and I kept saying, « This is not going to work in your gallery. Victoria is very conservative and it’s quite different from Montreal, » and he said, « No, no, no, I want to do it. » So anyway he gave us some money to start the caravan. That was our initial donation to start the caravan.

And then about three days later, I went to Vancouver to meet with David Silcox, who was head of the Canada Council of the Arts Section, and had coffee with him at the Georgia Hotel. He, too, had heard all about the evening in Montreal and he was equally as enthusiastic and determined to give us money even though we just had that reputation. We had a pretty strong reputation for Logos and that party, but anyway he went ahead and somehow authorized a grant for us.

I went into the library about two days later and I wanted to see the director of the library. I went in there and started pitching to him all about the idea of the caravan, and it turned out that, I think, he was the president of the board of directors of this foundation called the Leon and Thea Koerner Foundation. Lo and behold, this little old guy sitting in the library thought it was so fantastic that he gave us some money too.

So there we were sort of penniless and homeless, but we had all this excitement and these offers of money. So we ended up renting a farm in Sooke and we started building wagons and there were just crazy vehicles. They never worked. Anyway, we went out to this farm and we bought some horses with the money that was provided from these three sources and we started building wagons.

When we first opened up the first morning of the farm, there were about 45 people there. All summer long, we created a very strong level of discipline, because we had these horses and we had to work with the horses. So we created a work ethic that was quite strong. And by the end of the summer, there was only seven people left.

*

Cette entrevue, menée par Simon-Pierre Beaudet, fait partie du dossier Logos